“It doesn’t matter what it looks like,” he said. “It just matters that it runs fast, pulls hard and can survive in brutal climates. To me the Alaskan husky is the most amazing domesticated animal there is. Anything that can run 150 miles in a single day, nine days in a row and just live on raw meat and water is pretty impressive.”

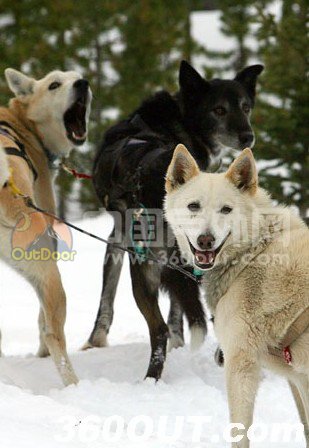

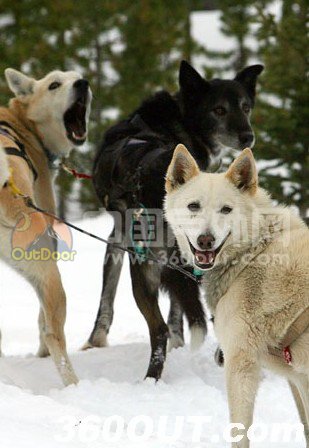

As Mr. Matthews parked his pickup truck and trailer at the trailhead, his dogs began to stir in the plywood cubicles. By the time he set out the sleds and laid out gang lines and traces, they had begun to whine and bark. As he unloaded the dogs — most of them 50 to 60 pounds — and we slipped on their harnesses, the dogs were in the throes of what seemed like joyous anticipation.

The dogs do what they are born to, Mr. Matthews said. “I think that sled dogs are self-actualized,” he said. “They have everything a dog could want. They can eat raw meat all they want. They can roll in the mud. They can run 20 miles a day. They just can’t help but to want to pull and run in a straight line.”

He put us through the basics of running a team. A brightly shouted “Let’s go!” sets them to running. “Gee” is right. “Haw” is left. A deeply growled “On by!” means to ignore the nearby moose or other distraction. A purposeful “Whoa!” is a hopeful signal to stop. Most important of all was stomping on the “brake,” a hinged claw at the rear of the sled that digs into the snow, with both feet — and then continuing to stand on it.

“Running dogs isn’t hard,” Mr. Matthews said. “Stopping dogs is hard.” He was sledding alone recently when he tied his team to a wooden United States Forest Service signpost. He stepped off the sled and the post snapped. “I walked for about five hours before I got to them,” he said. He caught them only because an iron snow hook had flown off and snagged a stump.

Finally, amid the tumult of yapping, snarling and barking, the dogs were hitched to the gang lines of the two sleds. We hopped aboard — one person riding in the basket of each sled, the others standing and steering on the rear runners. The dogs — 7 on one sled and 10 on the other — dug into the snow, straining at their harnesses, tightening the gang line. Mr. Matthews unclipped the anchor rope holding us to the truck bumper and our sled slingshotted down the trail. Seconds later, Mr. Herren and Mr. Wipf followed in the other sled.

We flew down a narrow trail and joined the groomed road that ran to the Beartooth Pass. As strong as the dogs were, they couldn’t pull through deep snow. To help, we would each kick with one foot as if on a skateboard. If the going was really tough, we’d take turns stepping off and pushing while running with the sled. Both man and dog tired at that altitude. Mr. Matthews said: “We’ll run ’em, stop ’em. Run ’em, stop ’em.”

Through the day, several snowmobiles passed. Most slowed as soon as they spotted us. “The snowmobilers seem to have respect for sled dogs,” Mr. Matthews said. “I’ve never had anyone get jerkish to me.”

The next day, on the Divide Creek Trail, we saw no one else. Through the early afternoon, the dogs tugged mightily to lug the sleds up a trail that girdled a mountain overlooking the Yellowstone River as it flowed northward from the park. As we climbed, big sage gave way to conifers. The spicy whiff of fir seasoned the cold air. Tracks of snowshoe hares crisscrossed the trail.

On a recent trip, driving sleds and dogs into a fierce wind, Mr. Matthews said he and his clients had startled a herd of 40 elk. As the creatures scattered, “my guests were ecstatic,” he said. “The dogs never even paid any attention to them.” Hearing the story, I looked for elk, but to no avail.

We ate sandwiches on the trail — literally on the trail, on two sleeping bags. We managed to turn the teams and sleds without tangling the dogs with one another, and headed back.

Now, the forest sped by. Dogs and sleds flew down the trail and around the curves. Far below spread the Paradise Valley, distant hills lit by the setting sun. It was a gorgeous, primal setting, the sort of wilderness best enjoyed by means of primitive transportation, so that we could see as the men and women of days gone by might have seen — at least as we imagined in our romantic fantasies.

Perhaps because I was caught up in such thoughts, or perhaps because I looked ahead to a turn down the trail, I failed to notice the left runner veering gradually off the trail. I stepped off the runners to run with the sled and wrestle it back on course, but I misjudged the depth of snow and both feet slipped out from under me. I gripped the sled as my torso and legs waved like a flag behind the sled.

“Whoa! Whoa!” I yelled optimistically — and ineffectively. As if in slow motion, we all — me, the sled, and Mr. Wipf riding — tilted to the horizon and burrowed into a snowdrift. Then the dogs stopped.

We righted the sled. I dug snow from my eyes, ears and pockets. This time I rode as Mr. Wipf took the controls, such as they were. We raced along. Every bend brought a new view of the Paradise Valley stretching north toward Livingston, until we finally could see the trailhead.

“I enjoyed every bit of it,” Mr. Wipf said. “It was more work than I anticipated, but it was well worth it. I think I might like to do it again some time.”